Little Joel and Political Cartoons: The Risks of Failing to Funny

Some of us are born funny, some achieve funny, and some have to publicly bare how unfunny they are to the public for three years to have a little funniness thrust upon ‘em

One of my favorite YouTubers recently posted a video about his thoughts regarding some recent pro-Kamala Harris political cartoons. His thoughts were not positive.

This YouTuber, named Henry, posts extended video essays about media and politics on his main channel “Big Joel” and his shorter, sillier, less researched, usually more casually critical and less rhetorically intricate posts on a newer channel, “Little Joel.” He started putting quick little commentary clips after Twitter took a turn for the worst: these clips are essentially tweets in the video format.

When I posted about this on Facebook last week, some of the (many! thank you!) commenters thought that I was characterizing Henry as saying that political cartoons had to be funny. I don’t think he thinks that. Henry’s critiques of cartoons’ humor were primarily aimed at cartoons that seemed to be trying to be funny and weren’t succeeding.

Similarly, many of the cartoons that earned the harshest criticism from Henry appeared to be making points the cartoonist thought were particularly amusing, thoughtful, or innovatingly or effectively expressed, but weren’t. Cartoons that were less than they thought they were.

Henry’s video raised the opportunity to discuss some questions I’ve had on my mind for a while: is it helpful to critique art from your side of the political spectrum when unity is key? Not critiquing the art on policy, but because you find it “cringe?”

Also—I started this essay before Henry had an extremely stressful incident while staying in Paris involving scammers and the handle of his door being hacked off with a saw and losing a safe place to live a few days ago. I apologize for the bad timing. I in no way mean to attack Henry with this piece: I think he has started an interesting conversation.

Henry’s off-the-cuff deadpan, sarcastic, fundamentally dismissive comedic style is perfect for not giving rightwingers the light of day. Right-wing hatred and staunch refusal to respect others’ freedom to pursue happiness doesn't deserve to be validated—and a dismissive, mocking style is perfect for responding to it. I genuinely enjoy his work and have followed it for several years.

Most of his criticisms of these pro-Kamala cartoons came down to the idea that they were redundant, absurd, not particularly useful, and not funny.

Henry, in his Little Joel videos particularly, typically uses a deadpan tone and wide-eyed stare that demands you expect layers of sarcasm and irony in most of what he says, and that’s certainly the case in his video about Kamala cartoons. As supportive commenters have frequently observed, his “rating system” for cartoons can be confusing: he’ll say a cartoon is fantastic—the best he’s ever seen—and then give it an 8/10. To me, this seems like clear evidence that he’s saying it’s fantastic… for a political cartoon. Adjusted for bad art inflation, if you will.

Adjusted for a piece of media that, as he says, is part of a “famously unfunny and uninteresting” art form.

That unlocked some insecurities I have as a political cartoonist myself, especially coming from a critic and humorist I kinda look up to. It also unlocked some questions I’ve had for a while but haven’t put into words.

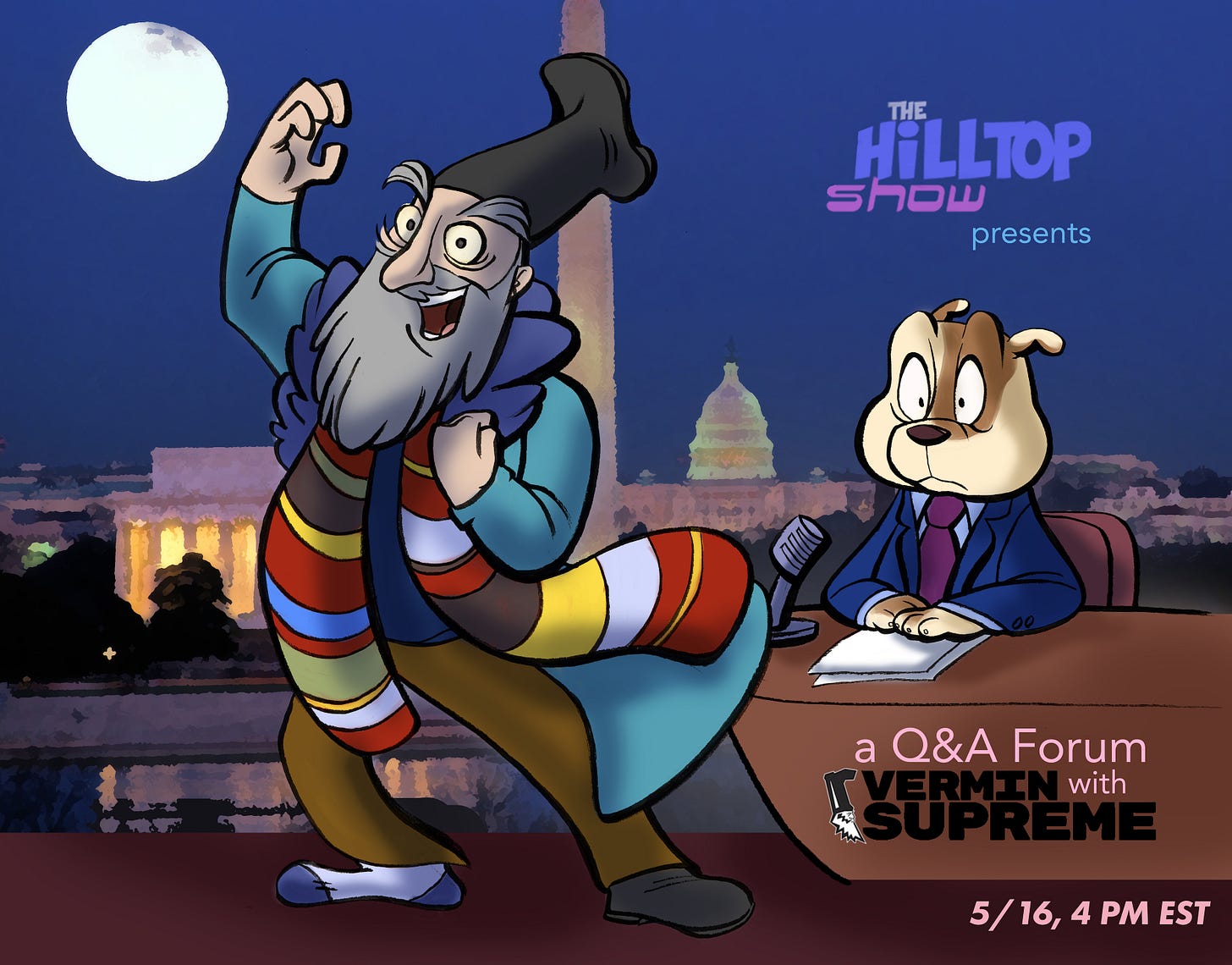

I started a late-night show in college called the Hilltop Show (I was at Georgetown University, known colloquially as the Hilltop). I hand-drew all the graphics and logos, which I was especially excited to do after making the Georgetown mascot bulldog into a little anthropomorphic guy in a blue suit holding a microphone. I drew him probably hundreds of times and put him up on posters all over campus. I put my furry art all over the Georgetown University campus.

Throughout my time running the show, other students both inside and outside the show told me it was cringe. And it absolutely was.

It took a vice president of the show to tell me that the time when graphics appear on the screen needs to be aligned with the words being spoken to make a joke successful.

I made no secret that I had created the show to get a job working on one of my favorite shows. I had a few hosts who were my favorites and incorporated their styles specifically. I used drawings of those hosts in our marketing materials, hoping that a drawing of John Oliver on a Facebook event would get people into our interest meetings.

I had a nine-foot-tall banner of the mascot and logo printed and had it in all of my Zoom meetings throughout the entire COVID pandemic.

I wore plastic non-prescription glasses from Amazon on my head because a) I don’t like having my hair in my face and haven’t since elementary school, and b) I thought they kind of looked late-night-y at the time. They looked like plastic non-prescription glasses from Amazon. And I do not wear glasses.

I tabled in Georgetown’s Red Square tabling zone and played "The Greatest Show” from The Greatest Showman on a speaker (albeit at a reasonable volume, I’m not a monster) while handing out flyers I painstakingly designed, which consistently had new furry art on them.

When I passed the show onto its new president I did a little Evita parody thing with an article called “Alex’s Final Broadcast” where it was super explicit that I was trying to paint myself as the fictional version, no less, of a real Argentinian demagogue, with not quite enough irony. I had just gotten COVID for the first time when I wrote that and was leaning really hard into the “girlboss in ill health” aesthetic. (I was actually genuinely scared.)

I can’t watch clips of The Hilltop Show. I struggle to look at the Instagram, even if the people who are running it now are doing a great job. I took a year to stop paying the Wix subscription because I didn’t want to log into Wix and think about the show.

I can’t even say the words The Hilltop Show out loud. I call it “The Show” to friends and hope they know what I’m talking about.

I’ve heard from too many people with vested interests in my professional future that it is actually a liability to be associated with the Show, and that I should delete the YouTube videos from my tenure entirely, I was wrong to quit the Georgetown newspaper to work on it (they say you can’t work on any other campus publications other than theirs, so I quit to start my own thing, thinking it would be better to have my own outlet to create the way I wanted), and despite what some people who work at the shows saying otherwise—that it’s good I did something at all—using this show as a professional bargaining chip is a recipe for hopelessness.

I spent the majority of my waking hours on this thing for three years and now it makes me sweat to even think about it.

Was it worth it?

Even if I applied for a ton of late-night jobs after graduating and have still been met with radio silence? Zooming out from that one specific possible end, was I at least being cringe with a positive result waiting for me at the end?

Absolutely.

Thanks to the Show, I know that, if I need to, I can pull out all the skills I pulled out there to pull off a project like that. I learned about my challenges and abilities as a leader.

I learned, at least a little bit, about how to recognize funny from not funny. For whatever reason, I needed to start out painfully unfunny in order to be a little bit more funny at the end of the day. Some of us are born funny, some achieve funny, and some have to publicly bare how unfunny they are to the public for three years in order to have a little funniness thrust upon ‘em.

The rest that I can take from knowing I tried to do something I wanted to do, and knowing that I did it the very best I could with the resources I had at the time, is wonderful. I am relieved that I did it and I take pride in having done anything towards following the impulse to take on a project that big.

By the way—the List of Shame I wrote out up there is a list of the most cringe things I can think of that I did during my time running the Show. And I bet there’s things I’m not even remembering, which ex-boyfriends are welcome to remind me of at their leisure.

I am proud of a lot of stuff we did. I don’t want to present the List of Shame as a sort of reverse highlight reel, suggesting that it was all or mostly bad. We made Breitbart mad at us and call me out by name. They called us a “Crack Research Team,” and you KNOW I made a whole line of merchandise out of that, furry art and all.

Georgetown University published two articles celebrating us. I won’t link them because humblebragging is not the point of this piece, but you can Google them if you want.

Since I’m talking primarily about the metric of funny: 90% of our show wasn’t funny by most counts. But we still accomplished some of those things. I don’t want to list more things I’m proud of out of fear I commit another Cringe.

I will say: as I was writing this, I did find myself at numerous points having to consciously avoid taking some pride in my work and the team’s work when that wasn’t the rhetorical button I needed to push in respective paragraphs. I think that’s a good thing.

Look ma, nuance!

Also—there were a lot of people working under me who worked very hard, and I don’t mean to disparage their work in the slightest. More than anything, I want to apologize, or at least own up to, leading them astray into Cringe as the group’s founder and leader.

But you know something about the Show? From what I remember, some of the people who thought we were pretty good were older. A few professors, a few friends’ parents: they went out of their way to tell me that they thought we were actually being really funny, and doing good work.

I’ve seen the exact same trend with both my past and current political cartooning work. The audience of my political cartoons is mostly older people. I recently published a political cartoon through Counterpoint that was grounded in an It’s a Wonderful Life reference—which is 78 years old—and it was far and away my most successful cartoon on social media of my four for Counterpoint so far.

I think there is such thing as objective funniness. Some humor is near-universally laugh-inducing (the “witch” sketch from Monty Python and the Holy Grail, the Seinfeld Soup Nazi sketch, The Emperor’s New Groove, and Enchanted) ought to cover everyone’s bases). Some is near-universally the opposite (arguably Sausage Party, the genital-related gags in the Cats movie, and, conversely Disenchanted).

It can also be true that something is written in the cadence of a joke but doesn’t strike the laugh-inducing landing—some things will be funny and impactful for some audiences and not others. Just because something appealing to a particular audience and isn't to another doesn't mean it's bad for what it's trying to be or shouldn't exist.

Older folks often think different stuff is funny than what Gen Zers think is funny. Older folks often like Jimmy Fallon. They often think Princess Leia "Resist" memes are funny. They often like Minion memes. And that's wonderful.

I took pains to make sure “often” was in every sentence there. No group is a monolith, especially when it comes to something as subjective, complicated, and culture-dependent as humor.

Gen Z folks may not find these kinds of cartoons for older folks, or without as much of a clear, biting punchline funny. But that’s not the point. They’re not for us. And political cartoons are an elusive art form to describe.

Gen Z humor, which I love, has a lot of requirements. At the risk of making a Barbie reference: Gen Z humor has to be sincere, but not too sincere. We have to use some lingo, but not too much. We have to be distant and cool, but not so much that we seem soulless. We have to be socially conscious, but not patronizing.

And of course, cartoons that spread misinformation--and I saw so many that spread misinformation about Imane Khelif, as just one example--should not exist. Cartoons that spread hatred should not exist. And MANY cartoons do.

I think too many publications are willing to platform these cartoons, excusing spreading them far and wide under the guise of “sharing views from multiple sides” and “well, this is just what the Republican Party is right now!”

Even so—hateful stereotypes are never helpful. Too many people are a little too quick to draw Kamala Harris as an animal as a means of mocking her, thus leaning into a time-old, all-too-common method of dehumanizing Black people and people of color.

But my ultimate thesis:

Even if the Hilltop Show wasn’t funny, is it good that I made it?

Yes. I learned about myself as a leader, showed myself that I can execute huge projects if I put my mind to it, and developed my comedic ability.

Even if political cartoons don’t always succeed in being funny when they are trying to be funny, is it good that their creators made them?

Yes. It’s likely that members of the cartoon’s intended audience do find it funny. If the cartoon’s goal was meaningful humor, the meaning element of the cartoon made the work worth creating because it expresses the creator’s opinion.

Even if political cartoons seem extra-proud of their ideas when they don’t warrant it, is it good that their creators made them?

Yes. Look past the window-dressing and look at the point the cartoonist is trying to express. Kind of like what my parents always told me about church sermons. It doesn’t matter if the priest is having a bad hair day or if their metaphors aren’t working. Those are distractions. Look at the core message.

Ultimately, if you think a cartoon is “cringe,” or nearly any piece of art made by a well-meaning, sincere person who is operating in good faith, you’re probably missing the point.

Of course, people who are trying to be funny can always work to be better. But especially when it comes to humor with a political point, whether something is funny or not is often a shiny object.

I genuinely do believe that political cartoons are important in our cultural ecosystem as a means of communicating complicated ideas quickly and simply. While that can be rife with rhetorical danger, it can make cartoons a powerful weapon in times when we need to be able to make clear rhetorical distinctions between good and evil.

If cringe political cartoons are going to get older folks out to the polls for Kamala Harris and Tim Walz and keep Donald Trump out of office, then let’s get the presses fired up to make as much Comic Sans-using, too-much-text-employing, ResistLib political cartoon glory as they can muster.

I'd like to think if you aren't looking back on your work and cringing every couple years, you're probably not growing as an artist.