Revisiting "Doctor Who": Canonicity Often Doesn't Matter and It's Better That Way

Conclusions drawn from failed efforts at objectivity around my favorite things

I wrote a prelude article of sorts a few weeks ago about how I was going to be watching through Series 6 of Doctor Who again to critically reevaluate it. I watched it in full last when I was a teenager, and did most of the watching while on a treadmill. I was a huge fan, and still am, and got just incredible joy out of the show, and still do.

I enter this piece with the thesis I was worried I’d have when I wrote my prelude article. Canonicity and plot holes in Doctor Who and elsewhere often don’t matter, and the show is often better for it.

Since watching Doctor Who Series 6 for the first time in full for maybe seven years (goodness), I have heard plenty of opinions about the Doctor Who revival’s quality, and one common opinion is that Series 6 is not especially good.

I actually didn’t realize until recently that Series 6, like the similarly-oft-bemoaned Series 7, is actually a two-part series, beginning with Part One: “The Impossible Astronaut,” “Day of the Moon,” “The Curse of the Black Spot,” “The Doctor’s Wife,” “The Rebel Flesh,” “The Almost People,” and “A Good Man Goes To War,” and ending with Part Two: “Let’s Kill Hitler,” “Night Terrors,” The Girl Who Waited,” “The God Complex,” “Closing Time,” and “The Wedding of River Song.”

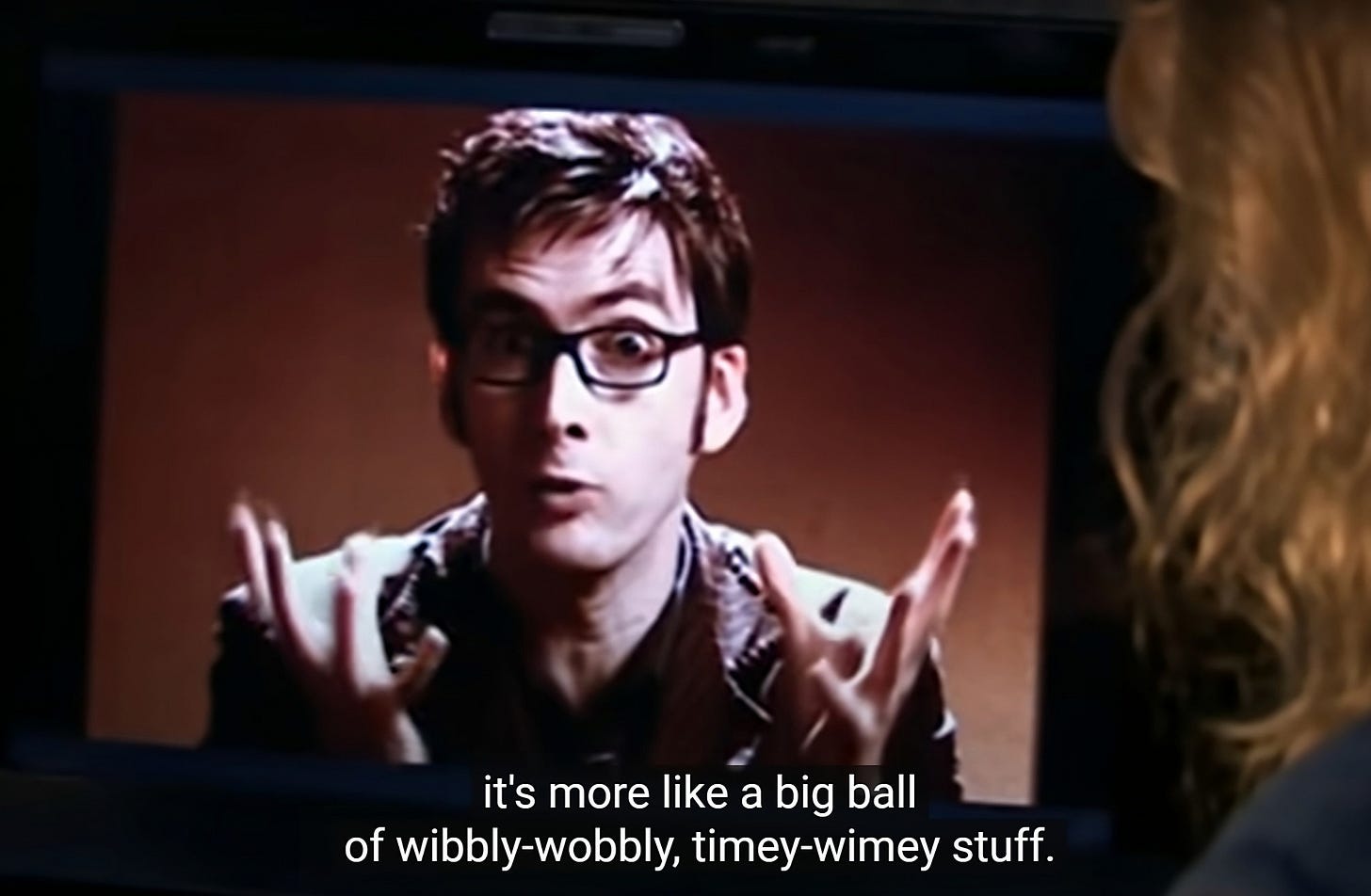

I thought listing the episodes would be helpful for getting an image of Series 6 in your head. I thought an image from Series 6 would also help get an image of Series 6 in your head.

Splitting the series into two parts makes sense: the first half deals with the River Song arc, and the second half is primarily comprised of miscellaneous stories and ultimately ends with a conclusion to the River Song/Silence situation that isn’t completely needed in addition to “A Good Man Goes To War,” unless you happened to care about the Silence, which the series’ final episode “The Wedding of River Song” sorta kinda wraps up. Not really. When I rewatched “A Good Man Goes To War” while working on this project, I forgot the Silence existed.

The primary criticism of Series 6, television which has been called “Moffat’s biggest failure,” centers on its sheer quantity of plot holes as a result of its (over?)ambitious complexity, specifically around various plot threads being left hanging and contradictions in episode arcs. These range from minor to significant.

With the series’ reputation in mind, I rewatched it, with my central research topic being whether a piece of favorite childhood media can be evaluated objectively.

Can it be done?

Maybe I’ll get better at it. But in this case, during this rewatch, the answer is no.

Were the plot holes so noticeable that it hampered my enjoyment of the show? Also no.

I found myself frustrated and disheartened by this. I had been hoping that somehow I’d grown up enough to poke holes in something I got and still get joy from.

I do know, inside, that the “Cinema Sins” ding-ding-ding method of pointing out continuity errors, no matter how small, no matter how much they really matter to a piece of media’s broad strokes, is bad-faith criticism. I know it’s bad for the way we engage with media. But that doesn’t stop me from feeling like standing above something I love would make me a smarter, sharper, and superior critic and consumer.

If I can pick apart something that’s whimiscal that I love dearly and was formative for my worldview by pointing out its logical errors, that means I got more out of my English master’s degree. I can say more new things that uplift our media discourse, while being paid, and being the center of attention.

Please subscribe!

Maybe I can make what I have to say new and worth listening to if I can stretch my brain enough to find new issues. Because, in fairness, who pays attention when you point out something new about a piece of media that’s positive?

But here I sit, unable to take those steps upward to where I could leer over things I love. Why? I just enjoy this show too much.

Oh, the shame. What is a master’s degree in English for if you’re not using it to write exhaustive criticism of children’s television?

This problem of enjoyment pointed me to an important light at the end of the tunnel. I genuinely found that Series 6 of Doctor Who was so consistently fun moment-to-moment that the plot hardly made a difference to me.

The show is so entertaining in itself, from moment to moment, that the plot making sense was barely necessary for me to enjoy it.

I think a lot about something my high school orchestra teacher, Mr. Mynes, once told our class. It was something along the lines of — ‘you can get every single note right, hit every staccato, blend together every phrase, implement every dynamic notation. But if you aren’t feeling the music, and you aren’t letting yourself fly with the emotion of the piece, then you’re going to give a bad performance.’ I hope I did the quote justice.

I thought about that line several times a week in high school and it still comes to mind when I’m thinking about media I’ve just engaged with, or my own personal work on a regular basis. Of course, sometimes in high school I used it as an excuse to not practice my cello fingering or annotate my sheet music as much as I should have, but it helped me get things in perspective.

And obviously, it’s possible to be the kind of person who notices plot holes and can still enjoy something deeply. I think my writing partner on this rewatch project, Brogan, who will be writing a reply to this piece on his Substack Consequitur (subscribe!), is exactly one of these people. He is an apt critic and observer yet remains a huge fan of one of the worst shows out there for canonicity… he got Doctor Who comics signed by Paul McGann at Long Island Doctor Who. He can still enjoy the show while remaining aware of its problems. What a guy.

We are all different. We walk into media with inherently different needs and desires. Some pieces of media just aren’t right for some people. But it’s easy to forget that, and dislike ourselves, or others who don’t want the same things from their media.

And yes, I absolutely think it would be good for my brain and professional skill set if I became better at retaining information about how a plot has developed and thinking about the writer’s central mission and execution on the technical end of their project. There would be huge value in that for me, especially as a critic.

I’ve been writing for DC Theater Arts for three years as of this month, and ever since I got started I have sought to make my reviews as helpful as they can be. And I believe I’ve generally done a good job. I recently got a lot of negative feedback from a cast and crew on a review where maybe I could have done better. I never want to shut myself down to the idea that I have space to improve. Unlike a few of those commenters who were clearly in that show’s cast and crew. I mean quack.

From one artist to others in a production, I want to help point out how we can make art that’s as immersive, and ideally transformative, as possible. Being able to find things to criticize in a narrative is core to this skill. But I’m not frantic to improve this ability to find loose narrative threads.

There is plenty of wonderful music, literature, film, and television that would get off nearly scot-free with CinemaSins — thank the Lord for that! — because they plugged most of their plot holes. A more specific example: There are plenty of musical performances out there that are technically astounding: you can hear every note. But the performer centers showing us every note and every dynamic over showing us who they are in their art. Is this kind of art everything it could have been? Does it make you feel something?

Are you drawn to your favorite pieces of art because they speak to something in your soul, or because they are free of errors?

Applying this message back to the blue box show: in my view, the issue of plot holes in Doctor Who barely matters if you’re there for the monster designs, if you are blinded by your nostalgia goggles and are just having a great time, or if you have a crush on the Doctor. I mean quack.

But seriously. If you are trying to get the attention of a bunch of teenage David Tennant and Matt Smith-heads on Tumblr directed towards the show’s continuity errors, catch a clue.

That intended audience, and so many others within Doctor Who’s fanbase who are less obsessed with those two guys’ dreamy eyes (I’m not immune, check my DeviantART from high school) and more with this historic show’s legacy and social impact, and so many others, are inherently uninterested in people who make it their mission to point out problems that didn’t make a significant impact on the broader episode, season, or show.

And so many times, I’ve seen critics jump from “this plot hole, or group of plot holes, ruined the episode for me” — an opinion!— to “this show was a complete waste of time” — an opinion disguised as a fact and ultimatum! These critics are usually younger, less experienced, and haven’t been schooled yet by a college writing instructor to cut the generalizations and strawmen.

But sometimes, on Twitter, even the good writers and balanced thinkers can revert to this kind of criticism in the heat of emotion about something they care about.

If you are so unpleasant, or such an imprecise writer, to make it your business to tell people that their favorite show is bad, straight-up, for any reason, it is either going to get you ignored or hated, with only a few exceptions for shows that are actually doing harm. You made people feel bad about their favorite thing being their favorite thing, with no practical benefit for them. What is the point in that besides attempting to inflate yourself?

And I say attempt, because usually attempts to inflate your platform online, in good faith and ill, fall flat.

I actually did a TEDx talk about this idea once, applied to the realm of political discourse, where, believe it or not, exchanges are frequently less heated than in Doctor Who discourse. I wrote and filmed this several years ago, so watch at your own risk.

Roger Ebert once said that if you’re having a good time at a movie, you’ll “forget your social security number and where your car is parked.” If a piece of media plugs enough plot holes that the only ones left don’t get in the way of you having a wonderful time, then what significant elements are there really to complain about?

I’m not saying not to criticize if there are things worth constructively mentioning in conversation or a written review. But I’m not talking to the balanced, thoughtful folks. I’m talking to the Twitter users.

And zooming out, Doctor Who itself is grounded in a premise that is hardly logical. The same character changes their face and personality to deal with actors’ filming schedules, and the show’s arcs are so often neatly contained within a nice neat set of 15 or so episodes, or 7.5 if Moffat is struggling to keep a plotline going for the whole 15. “Wibbly-wobbly timey-wimey,” which is a merch-friendly phrase for “continuity doesn’t matter and in fact, it’s more fun that way,” is essentially the show’s tagline. And by the way, Moffat, Series 6 showrunner, wrote it.

Paul Cornell, writer of the episodes “Father’s Day” and “Human Nature”/”The Family of Blood,” some of New Who’s best, summed up Doctor Who’s relationship with continuity and canon in his blog quite nicely:

“Not giving a toss about how it all fits together is one of Doctor Who’s oldest, proudest traditions, a strength of the series. It’s allowed infinite change, and never left the show crunched into a corner after all the dramatic options had already been done. Terrible continuity equals infinitely flexible format. It’s indefinability that results in that old ‘indefinable magic’.”

So if you won’t take it from me, take it from Paul.

At the same time, I stand by the idea that if canonicity issues get too severe, it can get in the way of that flow and enjoyment. The degree to which you value canonicity in Doctor Who depends on a whole number of factors of a whole manner of types. If you are a Classic Who buff, you might have more you’re watching for in the canon and lore than someone who isn’t (me, unfortunately). If you’re interested in time travel stories and their philosophical implications, you’re going to be paying more attention to continuity. If you don’t think women should play the Doctor, then maybe you’re going to be even more critical of errors in Jodie Whittaker’s era than it deserves.

I met her, by the way. She was wonderful. I have a photo with her and Mandip Gill where I’m in full Jellicle costume. And I didn’t even have to pay $200 for a photo because they came up to my table independently. I paid that $200 for the Jellicle costume supplies, though.

At the end of the day, let’s get things in perspective. Let people enjoy things. But constructively, kindly, and with a spirit of helpfulness point out when the things have too many issues for coherence. There’s a balance here, people.

Dr Who has always been about having fun. That is indeed a strength. Bad Wolfe year, Shakespearean actors wrestling with disembodied mannequin arms. What's not to love?

I am reminded of the line from John Cleese re a scene with Fog they wanted to reshoot, "Is the fog funny?"

In Dr. Who, they can routinely answer, "Why, yes it is"